India

30-09-2005

India – The Himalayas

August – September 2005

Finally, I have reached the endless ocean, called India. But first, as an introduction to India, I am going to share my impression from the Himalayas. Here, you are not going to find anything about Hinduism, magicians, saris, elephants, the Gang River, or anything else, that is typical for the plains. That is because the mountain peoples around the Globe are rather a common group of people, than a part of any other.

When I have the chance, I only pass through big cities. So, at noon, I spent only an hour at Shiliguri. It was at the end of the rainy season. Due to my laziness I did not take out my raincoat and I was drenched to the bone. Nevertheless, I managed to exchange some rupees and to buy a detailed atlas of India and the timetable of the Indian train system. I was always keeping these two books while being in India. They helped me much better than any travel guide. Travel guides inevitably put every tourist on the beaten tracks of this huge and boring industry. Several times I have overheard the almost forgotten Tibetan greeting „tashi delek“. Other mountain peoples, common for the region, started to be seen along with Indians and Tibetans: Nepali, Bhutanese, Sikkimese, and many more, all they dressed in their colourful, worn-out, and filthy costumes. I caught a bus to Darjeeling. The narrow-gage covers the same distance of 90 km for 6 hours. On top of that it is more expensive and operates once a day. It took me about an hour to dry up. Supported by stoneworks and walls, the road twists along the precipices were interrupted by numerous bridges and streams. If there were not any landslides the road and the narrow-gage interwound as they were mating snakes. Numerous non-sense signs were standing at the road turns. Presumably, according to their authors, the signs' purpose was to nail into every driver's mind ... if drivers were able to read. „If you are married, get divorced from the speed!“, „It is better done slowly in this world, than quickly in the hereafter!!!“, or just „Be tender along the curves!“. Around us, drivers of rusted buses and jeeps were slamming the clutch with a spontaneous tenderness and were revving up through smokes.

The rain became heavier just before my arrival, it was already dark. Darjeeling is one of those small and wonderful cities, with numerous hotels, where looking for shelter and impudent bargaining is a real pleasure. That is true especially out of the tourist season. I found a room in a house, whose first floor was on one street, and its third one on another. The steep mountain slopes were densely covered with all kind of solid buildings or sheet iron shacks. Only the open market was on a flatter location. The view from the terrace under the roof had to be towards the nearby Kanchenjunga. But during the rainy season, all around was somewhere behind the fog and the white clouds, that flow constantly and down-pouring. Within the next seven days, the world's third-highest peak popped up for only ten minutes. Such thing is a rarity, as the Nepali called Krishna said, after he woke me up at 5:30. The name Darjeeling means „thunder gathering“ , what is also understandable. I washed my clothes in the first day. While they were drying, I managed to do several walks in the surroundings – wearing flip-flops and a raincoat. I suppose that all the region around unveils its real beauty only after the middle of September, when the downpours perceptibly decrease in their frequency. The trails around the city can be hopped even on one foot. It is impossible to get lost; there are many roads with buzzing vehicles. The real Himalayan treks happen a bit in the northern Sikkim – an Indian autonomous state and former Himalayan kingdom bordering Nepal, Tibet, and Bhutan. Sikkim is open to foreigners holding 14-day permit, which is almost free of charge. The constant rain hindered my plans for the region. Many of the local Sikkimese – the Lepcha people – live here in Darjeeling. Besides working in the tourism they make a living in the local tea plantations. The Darjeeling brand of tea is world famous. One can see its production process in the numerous factories, which remind of roomy hay-lofts full of equipment. The tea leaves gathering, fermentation, drying, and sorting are trades, almost unchanged for centuries. While getting out of one of the tea factories, I saw an almost eternal sign. Similar ones might hang up somewhere in a Bulgarian provincial medical center – „On the 15th of August, we are not going to treat/evacuate broken drunken heads.“ August the 15th is the Independence Day of India. In addition, the cheap Sikkimese self-made alcoholic beverage was officially banned ... and in much availability.

“The wife of a Lepcha is also a wife of his younger brothers. The kids of that marriage, irrespectively of their biologic father, are children only to the oldest one. Obviously, the genes of the youngest brother are the most selected ones and according to our understanding, that archaic tradition favours him the most. There is no wife sharing between different families and it is uncommon to share her with a friend. Any woman rape is punishable according to the woman's status – the severest punishment is the penis cut off and the castration. In addition, the weight of gold equal to the cut off body parts is due to the woman's family and to the state. Only up to 3 ounces of gold is paid for lower cast women. The penalties for seduction are even less severe – the punishment is over men and women. The only examples of adultery, unrestrained sex, and bestiality tolerated by the law ... are during traveling” - this is a lose quotation from H. H. Risley's “The Gazetteer of Sikkim”, 18941 - one more reason for trekking long through Sikkim. Joking apart, the contemporary habits are not the same as those 100 years ago ... The inhabitants of those hard accessible lands, have barely touched the dynamic 20th century. Hence, yet, Sikkim bears its rich potential.

I have run away from the unbearable Bengali heat to reach Darjeeling. Now, running from the rain and humidity of Darjeeling, I set out toward Ladakh and Zanskar, 2000 km to the northwest. The weather there should have been dry and pleasant, but I had only a month till the middle of September, when the first snow falls and who knows how long more till the closure of the high passes, the chill and the winter. I booked a train ticket for Ambala and Chandigarh with great difficulty. Usually the berths are sold out weeks ahead. At least, I have learnt about the Indian railway system and how, in 95% of the cases, one can find a lastminute ticket. Forty hours later I arrived in Ambala, transited Chandigarh and after 4-5 hours I was in Shimla – the famous mountain resort and the capital city of Himachal Pradesh. The city centre is at The Mall Street and The Ridge – located at the top of the slopes. The streets are full of many shops and are bustling with local tourists. Street smoking is banned. Trash bins were available everywhere in the centre; everything was polished and ostentatious as if the head of the state was about to come. Only the carriers were giving the sense of nonsterility. They were carrying 20-30 bricks or huge bundles of wood upslope. The load was tied by strong straps. The carriers had put the straps across their foreheads or shoulders covered by thick towels, rags, and their sturdy palms, to make the deed less painful. Somewhere in the lowland, all the luster quickly disappeared; goats and monkeys jump on the tin roofs; the mud and the usual unparalleled Indian filth covers everything. After Shimla I reached Manali, which turned out to be a boring hippie and touristic place located on Beas River. Therefore, I quickly found the bus station for northern directions and bought a ticket for Keylong.

Keylong is only 130 km apart of Manali, but the bus takes the distance for 8 hours, not including the rests and the traffic jams. The gentle hills to the North become steeper and steeper. Sometimes, travelers run into sheer vertical walls with narrow streams-waterfalls. On the road, one could see mainly cisterns. They were supplying the numerous military garrisons in Kashmir. The traffic was heavy as this strategic and newly built road (it is an additional connection between Srinagar and Leh) was used for only 4-5 months yearly. Indians possess the talent to make incorrigible traffic jams, involving only a few vehicles in no time. No wonder, very soon, we were trapped on rocky twists between two-direction queues. The cars and jeeps around looked as scattered toys. Military trucks appeared and soldiers started to stroll through the crowd, arm in arm and bedecked with forest flowers. Just before being arrested, The Good Soldier Švejk puts on a Russian uniform to see how it fits him. The Indian uniforms were far beyond Švejk's vanity. After the traffic was stuck for more than an hour, several dauntless drivers of empty cisterns took the shortcut down the slope, along gravel-covered furrow toward the lower twist. They were followed by other cars and jeeps. All that did not ease the situation – the freed road space was filled with more cars. Finally, the military wisdom teeth went on foot upslope and started to stop the cars along the upper twists. About two hours later, the traffic jam started to ease. On Rotang-la, altitude 3,978 m („la“ means „a pass“ in Tibetan), our and the Lahaul/Spiti roads joined together and after a while the majestic Chenab Valley opened up ahead. The local Ladakhi do not shout and do not throw in the air pieces of paper filled with Buddhist preys, at the highest point of a pass, as the people from „Chinese“ Tibet do. Nevertheless, here too, one can see the typical threads with colourful banners, stretched up in hundreds of meters. The military staff kept several points on the road. Instead of checking the passports or passes, they only wrote down the foreigners' information into huge journals. The latter rot away probably unopened. During the same season, five years ago, I visited Kham and Amdo – two regions in northeastern Tibet. I can openly say, that to me, the opposite descriptions of „Chinese“ and „Indian“ Tibet in books and media, are only make-ups and intentionally distorted reality. It is hard to accept that the Tibetans in India are happy and free, but that ones in China unjustly treated and enslaved. As if only the Chinese have disposed their guns in Tibet and the monasteries survived The Cultural Revolution were 8, 12 or 16 (according to different sources). In 2000, I have witnessed a column of 250 military trucks in Kham. But in 2005 the Indian military in Ladakh were no less. During my visit to northeastern periphery of central Tibet I have entered about 10 monasteries. Then there were monasteries under renovation, a monk driving Mitsubishi Pajero picked me up, and I passed by a Buddhist printing shop. Both in China and India there were monasteries turned in nothing more than tourist attractions. Generally speaking, the monasteries in China are more authentic and untouched, so everyone clearly understands where the cradle of this original culture is. The fact that Dalai Lama set up his residency in the Indian Dharamsala changes only the cover of the things. In Keylong I had some food, drank the local moonshine and slept – all for $1.5. The next day early morning I continued by the same bus. There were at least 15 hours and maybe 200 km to Leh. On the map, after Keylong, about five hamlets are shown, but all they consisted of several entrepreneurs' yurts, where travelers toward Ladakh and Manali could have tea, soup, and food. In winter time the business disappears together with the last jeeps ... just before snowy roads become totally deserted. Bara-lacha La is in the mountainous region between Chenab and Indus rivers. High, snowy, 6000-m peaks show up again, behind the pass. The vegetation almost vanishes together with the nomads and goats. Seeps and rocks, carved cliffs and pinnacles, so peculiar for Ladakh, fill up the moon-scape of that „grand desert“. Chimneys made by the Wind sculptor remind of the remote Cappadocia. After a while, Zanskar blocks the view with its two higher than 5000 m passes. Further, the road descends into the Gia Valley. The Gia River is a tributary of the Indus River. One could cross Indus over a bridge at Upshi village. After since, there are only two hours and 50 km flat region left till Leh. The reader, who has not fallen asleep yet, will find out that I reached Leh in the early hours. I tried for a long time to find a Keylong-quality shelter. The things were tangled additionally, as there was no electricity at the time. Actually, Leh has lost its virginity to tourism long time ago. The mountaineers' hordes were already in the greedy hug of Kashmiri and Sikh traders, Indian tourist agencies, Ladakhi peasants, and dirt-blackened beggars, which could not be classified into any specific group.

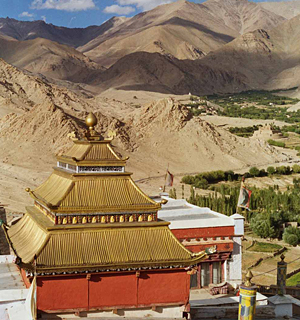

I am not going to mention any tourist attractions in Leh, as the interesting things were elsewhere. The administrative centre of Ladakh is located in a small basin at 3500 m altitude, between yellow, dry, and sandy hills, bordered by high and white mountain ridges. Indus River flows on southern side of Leh. The surroundings, similarly to Tibet, were in fact a high altitude plateau. In spite of the altitude, willows, poplars, apple, walnut, and apricot trees grow everywhere. All they disappear a bit bellow 4000 m. At this time of the year, virtually everyone gathers the harvest of barley, rye and wheat. It must be sufficient for the long winter (and world cut off) months. The apricot harvest dries up spread over rocks along with grass and herbs. A monotonous Ladakhi reaper's song is spreading over the field. Someone is singing, others accompany, everyone is loading bales over mules, oxen are stomping the golden sheaves. Herd breeders grow also goats, cows, yaks, and the so typical for Ladakh dzos, the crossbreed between yak and domestic cow. Besides cattle meat and milk, people also use the leather, the fur, the hoofs, and the tail hair. Horns decorate Buddhist rocks along peaks and high passes. People produce oil from the apricot's nuts – in the „desert“ almost nothing is wasted, everything finds its usage. I took a bus to Saspol, bought some ready made soups, tomatoes, paneer (Indian cheese) and chapathi, and shoved all that together with my sleeping bag in a small backpack. I crossed the bridge over Indus River toward Alchi. Crammed jeeps pass along the road; other tourists hire mules to carry tents, camp kitchens, neoprenes, heaters, high heel shoes, or ball dresses. For me, trekking is pleasure only if I do not carry unnecessary luggage. Alchi is a small village with a tourist monastery. Locals told me that Chiling is two days away. They also think the distance from Manali to Leh could be covered on foot for 3 days. I dragged myself the same distance by bus for 2 days. My route tied me to villages and staying at nights in local family houses. Therefore, as frequently happens, I quickly changed the route - „only a person with a final destination could lose himself“. On the next day I went back to Saspul, but I did not cross the bridge and went down along the river. The valley gradually enters a defile. Sheer cliffs appear on both sides after passing several poor hamlets. The lower parts of Zanskar range slopes are terraced by the peasants. Few kilometers more and the trail leaves Indus towards a small tributary and upthrusts gradually into cliffs and seeps (due to intense erosion, most trails in Ladakh go along river beds). Late in the afternoon I reached Mangyu, a small village with a unique location – over a high rock. I found a shelter at the local math teacher's house. The base floor of a Ladakhi house is most commonly built by stonework, either using mud or cement. Small paneless windows are vents in summer time. Round poplar beams are joisted above the stones. Branches are stacked above the beams. They are covered by soil - that is the floor of the first floor - the walls are adobe laid. There are several small sleeping rooms, according to the family size, and one roomy kitchen. Family members sit or lay on mattresses in the sleeping rooms. There are low tables next to the mattresses and (usually) filthy pillows are thrown around in disorder. The kitchen also serves as a living room. One of its walls is always furnished by shelves, where as in a pharmacy store, numerous copper dishes are stacked in lines. The water in the house is only what people have brought from the river or from the village fountain. The toilet is a room with a hole (sometimes two holes, one in front of the other) in the middle and with a view toward the base floor room. The human feces are valuable resource here as well. The doors, as throughout Asia, are too low – my head at several locations has become as hard as granite. After Mangyu, I went back toward Indus to buy food and took another Indus's tributary to the North. I had no idea where to find Yangtang – the next village. Late in the afternoon, I climbed a small hill full of partridges and found my way. I entered a big village, but it all seemed deserted, without any living soul. The white houses were inhabitable, but their doors were swinging, squeaking, and slamming, as out of an Enio Moricone's soundtrack. The only missing thing was the harmonica ... I headed toward the field, where all were gathering bales. My first impression of inhospitality was not a mistake. I found an empty and undamaged house, next to the dispensary. I gathered some dry twigs and piled them up on the cold floor. I got a shallow sleep and before sunrise I woke up frozen and having diarrhea. I made a fire and warmed up a bit. Before long some peasants came in to check what was on fire, but left soon. Early morning I continued toward Likir – one of the strongest corners of this part of the plateau. The monastery is worth of seeing despite the tourists and the view all around is wonderful. I spent two days in the region and finally, along the Zanskar River gorge and on a more distant route, I reached Chiling. Chiling is a village of two houses offering shelter, but no any staples. Indeed, this is the main problem in the region – if you do not tug several mules, you never know where there will be some food. The locals use their advantage and will offer you a meal for $5. Later they'll demand $5 more for a room. Nevertheless, sometimes, they will bring you to the cellar in a house, which does not look as a store and sells goods brought from Leh, with only 10% rise. There is no such information in any of the travel guides, thank goodness. Gathering such information by yourself is much more interesting, if you do not die of starvation or be dead frozen. An option: a mule costs over $20 per day.

Eventually I went back to Leh and removed off, as much as possible, my seven-day body dirt. I felt in heavens after eating two plates of momo (Tibetan dumplings stuffed with minced meat and vegetables) and bought a bottle of whiskey. I estimated the date was September the 5th and if I am not mistaken, I should have been traveling for one (not to say first) full year. I had a large gulp and twice knocked on the table. Till now I had no problems. The boredom disappeared within the first five minutes in Indonesia; I released myself from the European monotony during my first two weeks; I decomposed the last remaining bits of stress, this evil supplement to the watch, for one more month; since six months, my dreams were filled up by palms, monkeys, seas, volcanoes, and parrots (even my relatives appeared working on rice paddies, ships and stone quarries). For sure, I have changed my travel habits – frequently, I have started to take decisions where to head to right up at the bus station. I got used not to stop for long at tourist sites and sometimes did not even look for a contact with the locals. The traveling had become a reality, the time was flying as in a dream. Week after week I was drinking from the bowl of pure happiness and complete freedom. Soon, with the time, these ideas became hollow words – the basic feeling of living was enough for me.

I made a several day trip, starting from Stok – a village with a very large land despite its small population. I walked through their land at least for two hours. The houses are not clustered at one place, but built here and there, in the fields, almost as high as the seeps and falling rocks reach, along the road upstream, in the bed of a not so big river. An hour walk and the trail turns right along another stream. Dwarf pines disappear above 4000 m and despite the lack of any labeling, one easily can find his way by looking at footmarks, decaying tents, or camps' remains. No wonder that the locals can read the marks so well – for instance by content and consistency of manure, one can tell when, where, and how many and what kind of caravans have passed. I caught myself giving names to the marks on the ground – here „the pumps“ follow tightly behind „the moccasins“, and there they had stopped together for a rest, they had not carried any luggage, and over there, they had outstripped the sandals' „hyperbolas“ (seeps are an obstacle to flip-flops, but mountaineer's shoes are as much useless during summer time) of a tourist with a deformed left feet. If you possess the experience of several generations, you can probably decipher even the National identification numbers of the travelers before you. Yet, without any experience, footmarks are good, additional guides for the traveler. Stok Kangri, 6,137 m, stands in the sky on the left side. Climbing 500 m altitude more, you think you must be on the high pass. Instead you are in front of a massive obstacle, as it was the Chilkoot Pass in Alaska. The road's twists run along the steep, through seeps, diminishing and vanishing in distance. The remote caravan animals, just under the peak, crawl as an ant chain. The altitude demands – you often stop for more air, and finally, the wanted view is before you, opened up kilometres away in all directions. I met five Israelis, just at the pass Stok-la, carrying tons of luggage. Probably, the strangers were deserted there at 5000 m altitude, by their muleteers, due to financial issues. I did not have enough time to talk a bit, as I have changed my initial plan to reach the first village in a two-day trip to one-day one. Descending, with a slower pace I passed by Rumbak, Zingchan, Spituk and so on. One can plan trips in the region for the whole Ladakhi summer (trekking over the frozen Zanskar River is a winter delight). The sky darkened after my return to Leh. It was around September the 10th, and the sun did not appear anymore. My diarrhea terribly intensified. The symptoms, or rather their lack, were suggesting the Giardia lamblia diagnosis. My water filter was damaged before coming to Ladakh. During the first part of my visit here, while trying to fix the filter, I was drinking unfiltered water, adding to it iodine and silver nitrate. I started self-treatment with metronidazole. Three hours after the first pill, my permanent being on duty in the toilet stopped and the diagnosis turned to be probably true. Few days later, for sure, I was in a good health and took the bus back to Keylong. I was slowly leaving Ladakh and Zanskar, but the most interesting part of the trip was barely beginning.

I have reached Keylong in snowy and windy weather. I went back to the same cheap shelter and took my evening portion of momo and moonshine. On my ascending way I had took an unimpressive road to Manali and Kullu. The drivers now were talking about the same massive traffic jams, so I chose an unusual option – to continue along the Chenab Gorge to the West. My map shows a road reaching only Kilar Village. The travel guides do not even mention those amazing places. It turned out, after consulting the locals, the road reaches Kilar, only 90 km ahead. From there, one could go through Saach Pass toward Chamba or to descend through Kishtwar and Doda toward Jammu. It was raining for three days and I was sure it was not going to turn into snow in lowlands. But Saach Pass with its over 4000 m remained a big unknown. I took a bus for Kilar in the morning. I wondered why I bought a ticket only to Udaipur, 40 km from here. The bus turned smoking few kilometres from Keylong and we went back to take another one. Two hours later we were in Udaipur. We continued our way after a long break and taking a lot of locals. Five kilometers more and we reached a river, which has wiped out the bridge and the road. We stopped. The peasants waded through the risen waters toward the nearby villages. I also got off, the bus u-turned and headed back for Keylong. I asked the few people around whether on the other bank of the river there was any transportation toward Kilar. The people were not so sure. After smoking two cigarettes I also made a u-turn with the intention to go back to my starting point. I walked 3 km in the rain and exactly when I thought to myself my anabasis toward Kilar is over, an ambulance stopped next to me. The driver was Dr. Kalyan; his own driver had broken his leg and was lying prostrate on the back seat. Due to the rain they were trying to reach Kilar already for three days. Hundreds of patients throughout the whole region had been waiting for the doctor. The doctor himself has contacted people through a mobile phone and was expecting a jeep to help him in case of an impassable for the ambulance place. Fortune was good to me and in no time I seated myself with my backpack next to the broken leg. Dr. Kalyan stopped in front of the missing bridge and revved up the engine for a minute. It is good to look carefully where and how to force the river in such cases. Instead, the doctor slammed the gas to the floor and with power and luck brought the ambulance on the other side. We happily shouted for 2 km when we reached a tight place, where the road was blocked by boulders and gravel. Apparently, the road maintenance workers, which were a usual view in Ladakh, have decided to get out of their boredom by some dynamite, as either way, after the torrents and landslides, there was no any traffic. Dr. Kalyan called someone, who told him the jeep from Kilar was somewhere nearby. We left the driver with the broken leg to keep the ambulance and got through the blasted rubble. It was not so easy in spite of moving on foot. The jeep appeared after a while, took us and we went back. The jeep's driver was Nigi, a disabled clerk with his right arm withered and a dear friend to Dr. Kalyan. The latter seemed to attract as a magnet all kind of cripples. Only half an hour passed and the jeep was filled up by more hitchhikers. Ten kilometres later we were in front of a landslide where half of the road was missing. Apparently it was quite fresh one. On the other side of the landslide there was a car. We told the passengers it is useless to continue toward Udaipur. Half an hour later, in exchange to our kindness, they brought shovels and picks. Meanwhile we drained the water away from the landslide. Unfortunately there were only 2 metres stable width of the road remaining. We widened those two metres a bit and strengthened them by rocks and gravel. The left gorge's wall is maybe 400 m vertical for tens of kilometres. The cliffs on the right are more inclined. Through them a road is built two hundred metres above Chenab River. Above the road the height is as below – boulders, rocks, peaks and seeps, frequently carved by streams. We have almost finished with the picks when we heard a massive bang. I turned around and saw that a boulder, having a size between a washing machine and a church dome, have left a mark 5 m apart of me, and now was rolling down toward the river. Obviously all have noticed it – a second or two later, our group gathered under the shade of a huge cliff. In such moments, the instincts are much faster than thought and one acts as if dreaming. We waited a few minutes, went back on the road and continued our way. At some moment we stopped to have dinner in a dugout by the road. A local politician joined us – our chances to reach Kilar became real. Indeed, at about 10 pm the first houses appeared. The doctor drove me to the only shelter in the village, where I had plenty of delicious food. The rain was still coming down from the sky in torrents.

Saach Pass turned to be impassable. There, people say, was snowing and much snow has piled up. A jeep had to be rented until just below the pass. Later I had to walk for 15 km (wearing sandals in the snow) praying there would be some transportation on the other side of the ridge. Behind me were the wiped bridges, the blasts, the landslides and the rock falls ... It was perfectly clear to me if I decide to go back to Udaipur I could not rely on my yesterday luck and on Dr, Kalyan's mobile. So that option was crossed out. There were only three roads joining in Kilar and I had no choice except to continue toward Jammu – the human-made danger (even by terrorists) is nothing compared to the astounding power of nature. I waited for a few days. The rain slowed down but did not stop completely and using another jeep I reached Gulabgarh – 50 km to the West. On the road, we took in mainly military people and brought them to their posts. They looked round and pointed the left side of the gorge, where guerrillas have been skillfully hiding. Hemp was growing everywhere around – an everyday staple – people with no hiding were passing half-way smoked cigarettes. After Gulabgarh I took a bus toward Jammu and we were still in the Chenab Gorge, being a bit wider there. We passed by Doda Village (on the other side of the river), which is India-controlled only during military maneuvers. A few moments later it turned out that the same day in Doda, the army killed a financial mogul from the Hizbul al-Mujahidin. The first suspect arrested after the bombs in Delhi from October 2005 was coming from the same village. Nigi, the clerk with the withered arm advised me in short „Even a minute stay in Doda or Anantnag is dangerous“. So, after a week raining, I finally descended to Jammu. While staying there, people say, several bombs have exploded, but I have not heard them ... I was happy that I was out of the Himalaya's hug.

1. The avid reader is referred to: Risley, H. H., 1894, The Gazetteer of Sikhim, The Bengal Secretariat Press, Calcutta, India, p. 54 – translator's note.