Ethiopia: Specifics of the Ethiopian bivouacking

16-08-2010

March - April 2009

Man is a man when on the road, and somewhere in Ethiopia I turned my third human year and started the fourth. With no cake but very little ice cream we celebrate Teddy's “first steps”, and the country was an ideal place to unleash a whole arsenal of skills and instincts, picked up and practiced on the dusty roads. There was almost no preparation, and in addition to the very precise topographic maps from 1979 we had flight tickets, broken piggy bank and 3-month multiple entry visa. I thought that if we are bored we might jump to Yemen or Somaliland, but thank Thee - all worries proved in vain and at the end of the second month we were still trying to figure out what to fit in our nonexistent program. We took some bivouac inventory to honor the Ethiopian mountains and peasants.

In Addis Ababa we added to the inventory something I thought impossible to find there - butane/propane canister and camping stove and thus we got to know the city. The "New Flower" (as the name translates) of Ethiopia is new, but in no way can be called a flower ... or if it's a flower then it doesn't smell that well. No need to describe in detail the neighborhood in which we stayed - dazed by wild music, voices of wandering drunks and intrusive looks of prostitutes, but not intentionally ultimately I always end in this sort of places instead of the Sheraton. Only a small part of the city is built with atypical for Africa tall buildings, stores and asphalt roads, and everything else are informal gatherings of tin neighborhoods near gullies and trash deposits. However - a tin roof is a symbol of African prosperity and its presence in the villages near the straw huts is similar to a newly built mall in Sofia.

Every pupil can name the names of at least a few city-states, but when it comes to villagescountries we all have some difficulties. Looking at the Russian topographic maps before our departure, my eye caught plenty of small black dots lavishly thrown over the territory of Ethiopia, which stand for houses, huts, settlements, etc. - as if countless fleas had all jumped together on the map. I hadn't set foot at least till now in a country where nearly every wreck is at most 500 meters from the neighboring one and villagers could shout some not very lengthy news from one frontier to the other with the speed of sound. There are settlements of only 3-4 huts, but if you look around, on the hills there would be more and more, and people will pop up from where you last expect them. In fact, roads could be used only by mules and with the exception of a little asphalt between the few large cities, each commodity is transported mainly by the cattle, camels, healthy peasant or debilitated small children. It is excruciating to plow with oxen slops often reaching 30 degrees inclination, but it is routine for most of the locals, which, because of their isolation are constantly dependent on the moods swings of nature. It is not surprising that just one dry year in Ethiopia can waste 4-5 million people since the days of 80% of Ethiopians are equal to the number of drops during the rainy season - compared to that the donations for yet another crash Bob Geldof style look like vulgar and pathetic self-promotion. Still - if the cons of this self made lifestyle appears on the news in its ugliest form with children, flies and swollen bellies, the great advantage is .. independence. More than one or two aggressors have knocked out a few of their teeth in Ethiopia, and the yet not existing even a primitive control over the locals would have been awarded with a Nobel prize in various categories.

"The tourist is a person who destroys what he seeks - when he finds it". This axiom was formulated about 50 years ago by another type of man, who throw the insolence to descend alone with a raft of Blue Nile (Kuno Steuben book "Alone on the Blue Nile" unknowingly why translated in Bulgarian as "In the kingdom of the pharaohs"). I can not bear to pass without anger or contempt at least the dozens of contemporary travelers which burdened by high moral and equally false feelings are handing out pens and dollars to the poor African children with the attitude that this is the key to a better world. Beggar’s nature in children and subservience to "Mr. Birr" had entirely taken over this generous otherwise with impressions country, in contrast with my memories of Niger for example, or neighboring Sudan, where beggars still possessed the most elementary human dignity. After several days in Ethiopia we came to Dessie and Lake Hayk, where we planned to do the first bivouacking. Walked around the lake to look at the terrain, we saw pelicans, marabou, caravan of camels and local fishermen stripping the fillet from the carp, and then got to the first village. We passed through the main street and like in "The Pied Piper of Hamelin" we were surrounded by children. A couple from this house, 5 from the next door - and by the time we were leaving the village behind us trailed small horde of tattered kids. At some point one of them said "money", the second quietly spoke the magic word "birr" (this is the local currency) and an useable hysteria seized most of them beginning to compete who will stretch a longer hand. When we didn't gave up and continued on our way stones start flying around us. Same story repeated on the next village, and the third, and even above 3000 m (10 000 feet) altitude in Dessie. On the 5th day I start introducing to Teddy the theory that the only way to prevent the small kids from throwing stones at us is if we start throwing back - so we can at least keep them at a safe distance of 20-30 m. It is difficult to get used to the idea to keep from 4-5 years old kids the same way as you do with dogs (but without hurting them). On the 10th day in our camp we had full consensus on the matter and as soon we saw beggar kids we bent and reached for the ground. Do not reproach us - most of the tourists in Ethiopia move with guides whose purpose is to banish on their native language the covetous crowds always surrounding foreigners. And those who have been in NP Semien or Bale, where threat of wildlife or rebel movements does NOT exist, can confirm that tourists MUST hire a guide or scout with kalashnikov. No matter how strange - they only protect from the impertinence of the young Ethiopians. Compared to them - our native gypsies are as bold as choirboys from "Bodra Smiana"1.

I don't believe the tourists alone are to blame for this phenomenon, because most of them give away money in other countries too. The more we enter the local rhythm, the more we discover that Ethiopians were greedy towards each other. Bargaining for cents is integral part of the folklore of many countries, but Ethiopians manage to translate the very essential human relationships into favours and birrs. On the road there were hordes of innumerable breakers (calling themselves brokers) - people who waved at vans instead of local peasants who were headed somewhere, using their ignorance and fear of contact with the asphalt, city and civilization. Like the taxis in front of Central Station2, the breakers just thrust the peasants in the first vehicle, take 2-3 birrs from the driver, and then leave the passengers to their fate. It often turns out the van is going in a completely different direction, and when the peasant indignantly refuses to pay for a ticket, they are forced to pay the same 2-3 birrs the breaker took from the driver and then they are left on the road after only 3-4 km. I am thinking - for two months in Ethiopia we had only 3-4 conversation that did not end with "give me money for a textbook", "you are like father and mother to me" or "let me tell you about my story". The most interesting imbecile asked for 10 birrs for the time he talked with us, but we countered him with 15 because we talked more. I still can't find explanation for this typical Ethiopian phenomenon (and I have traveled quite a lot) but in the last page of Jack London's "Love of Life". After thousands of disasters and several weeks of fighting hunger, the main character is in safety - "They saw him slouch for'ard after breakfast, and, like a mendicant, with outstretched palm, accost a sailor. The sailor grinned and passed him a fragment of sea biscuit. He clutched it avariciously, looked at it as a miser looks at gold, and thrust it into his shirt bosom. Similar were the donations from other grinning sailors. The scientific men were discreet. They let him alone. But they privily examined his bunk. It was lined with hardtack; the mattress was stuffed with hardtack; every nook and cranny was filled with hardtack. Yet he was sane. He was taking precautions against another possible famine - that was all. He would recover from it..."

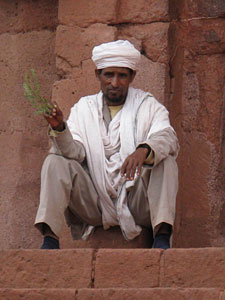

I am not going to write here about the religion of the Ethiopians and the carved in the stone churches of Lalibela. These topics have wide coverage in other reports from the region. But the very first night a group of children told us about the situated nearby "Ambua - upland" and Abuna Yosef (4300 m) - the top of the third highest Ethiopian massif. With wind up interest and applauding sleeping bags we headed that way. I need to write a few words about the country's climate which at that time was still quite dry. Because of its elevation, the vast northern part of Ethiopia has a very non-African climate. Addis Ababa is located about 2200 m and the days are hot as in moderate Bulgarian summer. There are almost no mosquitoes and the nights are very pleasant bellow 3500 m where is located the majority of the Ethiopian plateau. The place is ideal for bivouacking during our first hike we got lucky with calm, windless weather. Just in few hours we reached "first terrace", inhabited mainly by baboons, but when we approached to meet them face to face a guard came and refused to let us. The first terrace is separated from the plateau by a narrow stone ridge and his task to defend the turf was easy, but we disregarded him and boldly went on towards the baboons. When a second more insistent guard arrived and reached for stones we realized the game was becoming rough-and-tumble, so we gave up, coming up with only two explanations for the militancy of the guards - either on the terrace there were temples prohibited for infidels or they were sodomising the monkeys, which ... is not to be seen by tourists. We continued to the second terrace, and next week we found out that on the upland it is forbidden to cut wood and Ethiopians seem to have taken us for poachers with large backpacks. Human perceptions are prisoners for life in a small world, where "I" rules and often leads to paradoxes in the face of the unknown. A Pakistani few months ago said he wanted to buy a fake passport to come to Europe. I explained that he needs to spent a good chunk of money or the passport he gets will be immediately recognized with the new technology at the border. He thought dreamily for a moment and produced the following great answer – “maybe right then there will be a blackout at the border - and I will pass”.

While climbing the second terrace we got lost a little bit but the people form the next village consisting of 7 huts and 1 dog showed us the way. So in about 4-5 hours we got at a modest complex of thatched houses, which unfortunately will be opening doors for tourists. Rested, ate and continued with a small problem getting bigger ahead of us - how the hell do we get water? In all rivers (painted in thick blue on the map) in March, from the capital till here there wasn't a single drop of water and flat, round stones smiled at us from the dry riverbed. Finally, we noticed a herd of cows with muzzles in the ground and headed thereto. When we got close enough we realized that outside almost every village there is a huge puddle for the cattle. In the center of the puddle there is a circular stone wall and the center of the space behind the wall - there is a little spring. We stopped and while resting I filtered 4-5 liters so we had water for the night and then continued on the flat terrain. Abuna Yosef stood out in the distance so the direction was clear without the need of a compass. "Mountains" like that are rare where one hour scramble gets you to an area with the topography of Sofia field. In the distance yellow-brownish slopes fall down in waves from mighty cut plateaus, even out in the low and dropped down again to fall in the dry burnt rivers. At some point of the evening we stopped, which was inevitable, but it turn out to be a mistake. In only about 5-10 minutes we were surrounded by a squad of shepherds and shepherdboys, eyes staring at us. For people in the city was created much more boring TV, villagers have fairs and traveling circuses, the only diversity in the shepherds week, whether in Turkey or Ethiopia is to watch how a white man is preparing dinner - a campingaz, dry soup, chocolate and fuzzy water from packets of orangeade. Shepherds are hungry - they live in Ethiopia - but you will not give because your food is calculated till the last mouthful. And while 10 people drool 3 feet away from you gobble the only warm meal for the day, after the long walking, when you are hungry as a beast. Some shepherds put out even longer tongues, while others stare at your shoes and all of the hundred objects lying around as in a gypsy camp thinking how to steal them. One points to his feet - "Look at me, I'm barefoot, you have so nice flip flops" - a second one is clarifying - "The meadow on which you sit is mine... " - a third is getting to the point - "The water where your woman washes the dishes is ours. Give us the money". "Perhaps you'd also like the key to the apartment where the money is?" Ostap Bender would say, but we got away from the shepherds immediately, and they started snapping their whips after us. At first you get the feeling that a firecracker has been popped behind you, but these are just tails of the whips used to chase the cattle. Eeeh, Ethiopia - wonderful country with slightly odd hosts, which I would miss and will keep me warm for a long time...

The second night we slept at around 4000 meters, where we miraculously found a small stream. The water was frozen in the morning and the grass was covered with frost and watching Teddy's goose-down sleeping bag, I once again cursed my 7 year old sleeping bag with the thickness of a bed sheet. Although a peasant warned us the evening before that there is wildlife AS WELL we didn't see any specimens. Later on we learned that in the area of Abuna Yosef are seen mountain leopards and hyenas, but the rule of thumb for wild animal, always fleeing away from men once again proved true. Last year Teddy bought "dazer" that emits high frequency pitch that only dogs can hear - and she runs with it in the park. We went to Simeonovo to tease local dogs with it, but most of the mutts were deaf for the sound so we didn't have much of a success. My idea was that dazer might work on hyenas, so we had it with us in Ethiopia. However, when you are wrapped in 23 layers of clothes, sleeping bag and zipped bivouac sack you need about 5 minutes to pull out the dazer like a cowboy. I rather felt like frankfurters ready for hyenas. In a month time we tried the widget (invented to help American postman) in Harar and hyenas were not impressed at all, so don't go for it. Peak Abuna Yosef turned out to be a little hill above the small plateau of 4000 m shaped as a lying woman. To reach the summit one had to climb onto her head, and from there to revealed views of a long time dead volcano and stone waves going down in all directions. The animals were indeed rare across the massif, but the entire landscape was covered with lobelias and arrays of low, blooming in yellow and orange knifofias. Their color is similar to cob and is one of the attractions of all Ethiopian mountains. From the two species the protected plant is the lobelia - reaching 2-3 m high for 100 years.

Up to speed, we decided to go for a new bivouacking towards the rock monasteries in the area of Geralta. They are maybe only 300 kilometers away on a good asphalt road, but everything in Ethiopia turns to be more difficult than it seems at the beginning. And the intercity transport opens new dimensions for my favorite of all slow travel in unfamiliar areas. There is hardly another country where all long-distance buses depart from bus stations between 6:00 and 6:30 in the morning. I never understood this phenomenon, but no one drives at night and getting up at 4:00 is required. Bus stations open doors around 5:00, and in front of them have already gathered crowds of early riser passengers, with their heaps of baggage. When the doors open, everybody starts running towards the bus carrying what they can. Tickets and reserved seats are not sold off the previous day, so getting a ticket and a seat is like a lottery. While the passengers charge the buses, the drivers shout their destinations for orientation and a greater chaos stirs in the impenetrable darkness. Shipka3 epic take place at the doors of buses and for about 5 minutes all seats are taken piled up with bags, clothes and cheering negroes with broken teeth and aggression in their eyes. We came up with a system - Teddy is waiting with the backpacks outside the bus station, and I throw myself in the rugged battle and reserve two seats. After buying the tickets I get back to her, show the seat and climb on the bus roof with our luggage. Porters want to charge me 10 birrs for this service but I somehow get away with it at the risk to break my bones, then we drink tea, have breakfast and do our morning toilet. We traveled like this throughout all Ethiopia and only the tour of the North took us 40 days, given that sometimes we failed to get seats and had to repeat the lotto at 4:00 am next day. Buses often get flat tires, one bus dumped us midway, second one broke the radiator, a third one left us 20 km from the destination. You get used to it ... and in time we got exceptional schooling. The only carefree boarding happened in Shiro. I was first at the station gate and when it opened at 5:00 am I trotted towards the bus. Everything seemed very calm and wondered why isn't the huge crowd of Ethiopians chasing me, but at one time I felt somebody breathing in my neck so I accelerated my pace. He couldn't reach me, but then I felt more unusual details - nobody was shouting destinations and buses were dark, no headlights. I found our bus by the number, and only then I realized that I have raced with the drivers and announcers whose silhouettes emerged gradually around. And the usual commotion started, but at least we already had the winning numbers.

Geralta is often called the Ethiopian Arizona. Two of the villages have some primitive conditions for lodging, and we walked 15 km from Wukro and hitchhiked for another 15 km. We stopped in Dugum and quickly found comfortable place for bivouacking within the grounds of the local school. It is surprising that you can hide from the attacks of minors right in the school, but the system worked with daily donations of 10 birrs4 to the school guard. We encamped in the school hen house, with hens not moved in yet, and we got ourselves a comfortable shelter, the shoes, gas, saucepan and all other equipment kept in the nests as in cupboards. The place was surrounded by adobe wall, at least 2 m high, to keep us away from prying eyes, but we had to leave before the first lesson and come back almost at sunset. For the daytime backpacks remained in one of the two village pubs and the water pump was only about 15 min away. We borrowed a 20 liter plastic jerry can from locals, the second day children no longer stared so greedily at us, having realized that we don't need a guide, food or wood for cooking. At night, above us as in a huge planetarium were "rising" Orion, Alpha and Beta Sirius and the Southern Cross - very low on the horizon, and the views and talk were our "good night sleep tight". Rock churches raised inaccessibly in the verticals of mighty walls are just one of the attractions in the area where animals began to abound. I never imagined that in a dry country like Ethiopia could exist such a rich variety of mammals and birds, overshadowing everything known from West Africa or Ghana, for example. Rock damans were looking at us through the thorns of cacti, hoopoes and feral rock pigeons live in the trees, falcons flew in the sky, and in the low land camel caravans pull off or pull in from somewhere. Rabbits leapt from under our feet, mice dived into their holes on our approach, and domestic animals also wandered around, followed by shepherds with cracking whips. We didn't see snakes, but lizards were all over the place, bats with pig snout hung from the ceiling in deserted churches. The most beautiful church is definitely Abuna Yemata - high in the cliffs could be reached with 40 minutes hike, 10 m climbing with steps and holds in a sheer wall and 10 m on a narrow platform without railing over 300 meter gap. Monks and priests have the technique of chamois, but in the church go most ordinary mortal from neighboring villages, with infants on their back to be baptized. On our way there after several hours of walking, we cursed the 3 jeeps with tourists who turned at the foothills of the church at exactly the same time. Around them were cruising sufficient amount of vultures - guides, porters, helpers and beggars. Tourists explained that the priest with the key from the church had not yet come, but we didn't need the priest so we rushed up hill. Some stranger walked in our tracks and Teddy in simple words explained that we won't give him any money. The local continue to follow us, Teddy continued to send him away - Where are you going? Birr yelum (no money), get out of here!" To our surprise the man began to pray in front of a dry tree and even helped us at least with moral support on the 10 m vertical key point of the rise ... We were pushing off the priest, but Christian faith and stoicism helped him to endure us.

Christianity in Ethiopia is slightly odd. Same as the local Amharic language, full with words similar to Arabic (they are still in one group) Christianity and Islam also intertwined here in something not typical for the original sources. "There is no Hindu, no Muslim" - said Sikh Guru Nanak Dev, bearing in mind that all people are human first ... not even having been in Ethiopia. Churches are usually with two entrances, one for men and another for women, and to take off the shoes at the door is also not very typical elsewhere. From my long stays in Istanbul was used to the early wake of the muezzin, but here (when there was electricity!) Christian cranked up midnight prayers on megaphones and things were not easy. Women at the service all sat shrouded in white, and when we happened to be at Easter on a desolate plateau in NP Bale our guide told me - "Stay a little! Today is Easter, I have no one to talk to and I feel lonely." "But you are Muslim, Idris" - I replied and he explained that only his parents were strict Muslims, that he didn't pray and Easter was the biggest holiday in the Ethiopian year for all peoples and all religions. Long live Easter - we honored it, couldn't do otherwise...

Our next stay in the mountains was NP Semien. Better not to describe the difficulties we had getting from Axum - the road is in terribly condition, and public transport in this particular segment is still in its infancy. We rode in the cab of a truck with three people chewing chat - Ethiopian drug nationwide - and Teddy was rolling "comfortably" in driver's bed. The road veered in coils up to about 2900 m to Debark (entrance of the park) and all the places that were previously lost in the dark clouds over the mountains in just few days appeared 1000 m below us. As I mentioned, we had to hire scout with kalashnik (40 birrs/day), and weather made me carry tent as well (30 birrs/day). Despite the fact the scout who came to introduce himself didn't speak English, I explain to him that we will travel the first 20 draggy km with public transportation, that he doesn't have to come with us to the very top, and that we will take a truck on the way back. Scout Mulau was at first surprised and hesitant to disobey all these forced by the management rules, but next day he himself hurried us not to miss the bus. The tourist were supposed to hire jeeps in the park where there were at least 50 villages and all kind of transportation - who are they to say? (considerable advantage of the unsettled lifestyle is the ability to comply only with your own principles and conscience). The first day we passed the first camp and went straight to the second - Gich camp (3500 m). The hike was long and exhausting, but at least Mulau's kalashnik was well respected by all beggars. The second day we devoted almost entirely to chat among baboons in Imet Gogo (3900 m). Chat - social drug in the form of green leaves with a slightly bitter taste. The older leaves did not produce juice and were no good to chew, and the only effect of young plants and quantities less than 1 bag was loquacity and mild euphoria. Moreover chat suppresses appetite and has proved particularly suitable for the combination of starving countries, long mountain hikes and Easter fasting. Family package costs about 1 lev5. Herds of baboons jumped a dozen yards away, but sometimes we feel that tourists treat baboons same ways as Ethiopians treat tourists because when pointing the camera to them they turned their back as if saying - "do not bother me"! The encounter with the Ethiopian Red Wolf was postponed for Bale NP, where there are more specimens, but we saw 30 meters away the endemic walia-ibex (30 meters) which has also reached down to 300-400 animals total on the Earth. The plateau at places drops 1000 m down and the waterfalls even in dry season are ... impressive. The distance to the walls had deprived this region from alpinists, but also the escarpments are very often crumbly and unreliable. It doesn't prevent the baboons who live in whole villages in the slits of the rocks to start off in the morning on the monkey freeways towards the plateau. The terrain is very broken and denivelations prevail - so say, the day before Ras Dashen (4500 m - highest peak in Ethiopia) we had to go to a river at 2800 m, and the next day from the same river for a few hours to climb to Ras Buahit - at 4000 m. In general, the location is ideal for training with heavy backpacks, and a man has the opportunity to contemplate the whole day route in front of himself pondering on his own insignificance and... fall. Even at the highest point of the array we had the feeling that one tip a kilometer to the southeast is at least 50 meters above us, but because I have many times fallen into such errors I did not dare question the guides led the tourists to the more accessible under peak. Somebody has to go there with altimeter. On our way back, as I predicted, we got a truck. During the first 10 km he was almost empty. We sat in the lowest part of the back and Mulau covered us and our backpacks with rugs and blankets. Apparently he was afraid that could cost his license, if they found us. On the road the truck was filled with standing Ethiopian peasants who couldn't know whether the living things in their feet were humans, chickens, goats or something else. From time to time we had uncover our faces for some air and arriving in Debark, Teddy with her exceptional standards of cleanliness remarked that does not approve of the taste of Ethiopian farmers toes. In Debark there was water and food and draft beer to reset the receptors with.

They say Ethiopian cookbook is one of the thinnest in the world. This is not true - it has whole 3 pages. On the first one undoubtedly is presented the injera. Not only that most of the animals are endemic in Ethiopia, but also the teff - the cereal plant which is used to prepare injera also grows only there. Very tiny anemic and sour - hardly anyone else (except eritreans) use it as food at all, let alone nationwide. On a thin pancake called injera they put tidbits of vegetables, meat and even pasta - plenty chili to ease all this to go down the throat. At the bus stations mostly one can find kolo - I guess kind of roasted barley. Locals eat it same way we gnaw seeds and our scout Mulau could go on indefinitely in the mountains only on kolo. On the second page of the Ethiopian cookbook are spaghetti and macaroni, which here are called pasta. The sauce is chili, but sometimes - just salty. The third page is fully dedicated to the egg - fried, scrambled, and even poached. That's that - during the fast there was almost no meat, scarcely eggs, so don't ask what did we put on the table. From time to time we indulged in fish, fruits such as papayas and mangoes were needed daily. Beer as well - as the only reliable source of calories. In principle, I rarely drink when traveling, but beer in Ethiopia became a self-imposed diet. Poor people drink Tala - beer from fermented green leaves, and a boy said he had to drink at least 3-4 to "get the message". Besides the Tala, many locals with mutated eyes rub the benches in the Taj-houses all day long, where mead is served with the taste of wild wine or the very strong canary concentrate in transparent tubes - also made of honey, that is what "Taj" means. Teddy announced the Ethiopian honey to be one of the finest she had tried, and similar to Mulau fed in Semien mainly on honey... and to the peanuts and chocolate which I carried in industrial quantities she looked with contempt. Mulau did the same. Coffee however is superb with unknown to Europe fresh scent of nature, perhaps outranking the Colombian. Indeed, tourist are not well taken care of in Ethiopian restaurants - all on the menu is written in some unknown language like Amharic, and if you ask the waiter - What do you have to eat? - they always answer - "Yes" and this is the only English word in his dictionary. From there on there is no misunderstanding. No matter what you order - always comes injera, pasta or eggs, accompanied by some arbitrary and inevitable variation on "chilies".

I did not expect to find so accurately preserved medina in orthodox Ethiopia. Harar still maintains the atmosphere of the Islamic Cultural Center of the world, not inferior in anyway to Malian Djenne, Moroccan Fez or Egyptian Al-Azhar. The city wall is slightly tumbled-down and only a few gates give an idea of the glorious past, and the narrow streets winding between painted with strange symbols houses reminded me of the views in Nigerian Zinder. Markets here offer mainly chat since despite Koran the nature gifted the surroundings with first grade drug. Richard Francis Burton and Arthur Rimbaud are only two of many travelers, who devoted several years of their life to Harar, assuming the role of merchants, trading arms, slaves, or hashish. And, like Timbuktu, Harar for long time has been banned for infidels - and circumcision was only small part of the masquerade, which the curious had to subject themselves to. Today’s curious come in buses to attend another tradition turned into a spectacle for tourists. In the evening if you leave Harar from the Yemen gate and keep to the right, just in minutes you will arrive to a 3-storey shelter for lepers. In its surroundings numerous mutts are rolling on the ground, but approaching them you will distinguish the spots on their fur. Their bodies also grow and thrive, hind legs reduce and at some point you will realize that this is a pack of hyenas. Good news is that they are tame. Belief is that people began to feed them in the years of plenty to prevent their attacks during draughty periods and as a result - hyenas accustomed to the ritual, and today are almost part of the squads for cleanliness of the city destroying huge piles of garbage. Salomon is one of the dozen hyena-men who every night (when tourists come) takes out buckets with gristles and skin for his four-legged brethren. Then he hangs it on a stick, puts the stick in his mouth and 10 cm from his nose snap the teeth of the spotted pets - training their jaws to hang on a bone indefinitely. The sounds hyenas were making 20 m from the hotel were impressive. At night their dense as fire engine sirens voices mix with the barking dogs, crying babies and screaming nervous parents. Shortly thereafter, megaphones started the Islamic prayers and patter, but still the whole cacophony was preferable than to hear the memorable dense voice in the mountain and reach halfhearted for the "dazer".

Somehow we failed to get informed if there were hyenas in Bale or not when we headed to the to second highest mountain massif of Ethiopia. The 150 km to Dinsho (entrance to the park) we took without a flat tire for just 7 h, and the village welcomed us with rain that made the streets into mud so that if we were in flip flops, they would inevitably remain a gift to the archeology of the next century. Contrary to the warning of the weather, I didn't like the tent I was offered and decided it would be folly to rent something that will just add additional 5 kg. Unlike the dry northern Ethiopia, the meadows around shone in deep green, and the long plowed fields of the peasants also looked abundant. Then began the bargaining - we had to rent a mule. Had to hire one mule (we had less than 45 kg - thank Thee), but if your luggage is on a mule, you are obliged to hire a second one for the guides luggage. And if there were two mules we needed muleteers and cooks, and more mules for their luggage. In our heads mules multiply as rabbits and service staff has grown to the size of a Himalayan expedition. Fortunately, the provision of the rules in the national park hung almost over my head and there all this ritual began with the magic words "if you decide to hire a mule ..." That ended the discussion, a few days after our guide in almost depreciated shape complained of severe back pain. Idris was racing with mad pace to get faster to the camps and allow more time for resuscitation. This was the second time during his 5 year career when he had to carry his own backpack. On the other hand we have never trusted some unknown mules with our luggage therefore we always carry everything on our backs.

The topography of Bale can hardly be called a mountaineous. But the not demanding hikes on the vast plateau above 3000 m are usually accompanied by meeting with so many animals that walk is almost in the category of a safari. Above us we could see the roof of the national park at 4000 m formed by long frozen giant lava flows, and among the many rivers of the region were not present the typical Ethiopian villages. After the first flock of ibis and herd of green baboons, the red wolf finally came to meet us. Many years have passed before it was genetically proven that is just a wolf, not fox, jackal or something else, but the animal was very beautiful with high suspension, elegant gait and the grace of a gazelle. Dozens of stray dogs are their only enemy, but zoologists said that they lost 100 of all 400 in the reservation because of rabies last year. We got lucky with the weather and when we made our sleeping bags under the shelter of the zoologists, listened for a long time how the drops of rain beat on his straw roof. In addition, the climate this time of year had already become cold and windy and this was not helping the bivouacking. I have to admit that right there a guide might be justified - even though the directions were extremely clear, it was not easy to find the camp hiding behind a rock in the plain. True - there were maps, but they mostly sealed the inefficiency of their makers. On the second night we started to look for caves and holes under the stone, which was our only chance to stay dry and sheltered. Climate resembled that of the Andes - there was no escape from the afternoon rain, and the midnight drumming was sometimes accompanied by lightning flashes. The third camp was already over 4000 m where the vegetation is scarce. I think I wrote how we celebrated Easter with Idris, and later found out that almost as lonely have been on the holiday the endemic Ethiopian fleas, whose traces we manage to loose not before our arrival in Europe. Local shepherds would come in these areas only after several months when rainfall is significantly higher, but the jumping bloodsuckers live in their huts the rest of the season from the handouts of muleteers, cooks, guides and people like us. I do not know how many fleas did we take with us down to the hut, but I whole-heartedly wish the cleaning ladies have managed to wipe them out without the help of "Cyclone B". When we storm the peak, the weather was extremely stable, cold and fresh. Gentle breeze was blowing in the morning and we quickly crush a long distance before we see something familiar from the central Balkans. Tulu Demtu (Red Peak - 4300 m) is the counterpart of Botev peak, and we were coming up from the west. We stopped and left Idris with the luggage and on account about how long was the hike from Botev shelter to the peak and back I told him - "Idris, we will be back at 11:00. Be ready to go!" I think the only difference between the two peaks is the two kilometers denivelation and Tulu Demtu is also covered with dishes, but military. The wind was unbearable around and I tried to butt in with the guy with the gun, but he most conscientiously refused to let me into his small guard shack. At exactly 10:50 we were back to the guide who boasted that three wolves had passed him barking for long time. But howling or barking are only misleading words - sounds emitted by the Ethiopian wolf can be likened to the hoarse croak of a bird. Even confused with it.

The next fourth camp at about 3 h from of the Red Peak was the most beautiful - huddled between two rocks above the caldera in a field of yellow, orange knifofias. Nearby there was a hill, whose surface was burned by lightning, and the pastoral landscape around the local shepherd’s huts abounded with countless beautiful polished raven black obsidians. We were somewhere at the crater of this long forgotten giant volcano, which poured his insides into everything standing up around today. I thought of Indonesia's Tambora - shortened by as much as 600 m after its last eruption - and decided that the volcano here was probably 5000 m. We were seeing wolfs everyday now and memorized with the camera at least 10 of them for future generations, and the path went down and back to Dinsho, passing the mineral and iron and manganese-rich springs. Our last bivouacking we did on grass, in a comfortable and more romantic than all French castles rock hole at 3500 m. Difference in height was immediately sensible, as we slept without bivouac sacks, and almost naked. As if the weather had stopped casting us away; we were leaving and on the sky was sparkling this truly memorable interstellar landscape giving of itself with such beauty only over warm countries. And towards Tulu Dimtu the sky contrasted - completely black and ragged, it hung as a heavy hellish silence, interrupted only at moments by thunder.

The time has come for rest ... and sauna. With the invaluable help of Teddy I brought 40 pounds of wood for 40 birrs along the 2 km between Dinsho and the shack, and there we indulge in (censored), food, bath, beer and lavish servings of noodles, canned fish and mango. We said goodbyes to Idris, but still remained another day at the park to walk between nyalas, wild pigs, menelik bushbuck (not sure if endemic too) and colobus (monkey species without thumb - its absence is offset by long, white, fluffy tail). Animals often stopped just meters in front of us and looked with their warm eyes, and we walked in the enchanted forest like two oblivious children on their way through paradise. And if sometimes you/we think that we haven't returned to Bulgaria - it's because we are still there.

1. Popular Bulgarian children choir

2. Sofia, Bulgaria

3. Crucial battles with many casualties were held at the Shipka Pass during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

4. 1 BGN or 70 cents

5. About 70 cents